It’s the solstice (or it was when I started writing this), and once again, druids are convening at Stonehenge to celebrate. Good for them. Historically inaccurate of them, but good for them nonetheless. After all, there is a long history of people re-using the sites of previous religions to celebrate the rituals of new ones and, while the ongoing, amazing discoveries of the origin and context of Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments are fascinating in and of themselves, it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that, without modern Druids and other pagans kicking up a fuss, people wouldn’t be as interested in doing–or funding–all that research.

But who are these druids, and how did they get the idea that Stonehenge belonged to them?

THE IRON AGE DRUIDS

I’ve long been interested in the ways people’s ideas about classes of individuals such as druids and witches have changed over time. Druids are the trickier of the two, because it’s impossible to state with absolute authority what, exactly, they were up to when they were a living element of Iron Age Celtic society. This is because, for reasons that apparently made good sense at the time, druids made a deliberate choice not to leave a paper trail, or much of a stone trail, or etched-on-metal-trail, or (probably) a scratched-onto-wood trail. You got the transient, ephemeral, spoken word from them, and if you didn’t remember it, tough luck. According to Julius Caesar–a biased witness, but you make do with what you have at this distance–druidic education consisted of 20 years of memorizing poetry, in which was encapsulated their religious, scientific, historical, and legal knowledge. Other classical commentators compared Celtic priests and their religious beliefs to those of the ancient Persians, Egyptians, and Hindus. Unfortunately, exactly how they are comparable is usually not very clear.

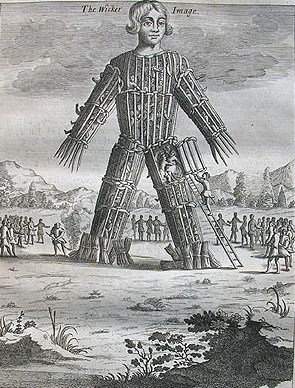

However, we can make some reasonable guesses. For instance, in terms of structure, the Celtic druids are grouped with the Persian magi, the Egyptian priesthood, and the Hindu Brahmins, which were what you might call organized, educated priesthoods: this was not a case of an inspired individual taking charge of a tribe’s religious life, like a Siberian shaman; or of a ritual position passed on solely due to inheritance. This was something you went to school for, something that had a hierarchy and specializations and some kind of international confraternity. Druids seem usually to come in flocks, a chief and an entourage. Sometimes, perhaps in their judicial mode, they sacrificed people–maybe.

The classical comparisons in terms of religious content are to other Indo-European religions–interestingly, to the easternmost Indo-European groups, the Indo-Iranians. But it should also be noted that, as the Roman Empire spread to encompass Gaul and Britannia, local deities were assimilated to Roman ones with, it would seem, relatively little cognitive dissonance for their worshipers. Sulis, the local goddess of Bath, turned into a form of Minerva; Mabon, “the divine son,” was worshiped at Corbridge as Maponos, Maponos Apollo, and Apollo Maponos. In other cases, a Celtic deity (often a goddess of a river or spring) was “married” to a Roman one and the pair worshiped as a divine couple: Rosmerta and Mercury, Sirona and Apollo Grannus, Nemetona and Mars Loucetius (the latter two male deities already assimilated to Celtic local gods). However, of all the Celtic deity names preserved through Roman inscriptions, that vast majority occur only once, and most of them appear to be associated with places rather than general concepts: a goddess of this spring, not the Water Goddess. So it is reasonable to assume that the druids were probably not that different from the Roman priesthood, either, and that their religion was part of the general pattern of Indo-European belief, with a a belief in some form of reincarnation rather than an afterlife and a penchant for localized, place-bound deities. The closest thing to a pan-Celtic deity, based on slim but geographically broad evidence, was Lugh, the many-talented god with shoes on.

In addition to their role as religious functionaries, however, druids also were counselors to the king, judges and lawyers, doctors, astronomers, historians, poets, and teachers–the Celtic professional class, the people who were

not warriors, farmers, or artisans. (The most convincing evidence, to my mind, for the identification of

Lindow Man, the peat-preserved body dug out of a bog near Manchester, England, in 1984, as a druid is that he did not have the musculature of a warrior, who would have over-developed muscles on his sword-arm side, or the scars that would be the inevitable result of working with your hands, either on a farm or in a workshop. In other words, he had the body of a man of thought rather than action, and at the time and place he lived, that means druid.) In many ways, the organization of druids seems to me comparable to that of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge prior to the late nineteenth century, when all Fellows were,

de facto, clergy of the Church of England, even if they actually spent all their time on Latin love poetry or turning alchemy into chemistry.

POST-CHRISTIAN DRUIDS

Where we have written accounts of who the druids were and what they were up to, it’s always from outsiders–first the Greek and Roman historians and ethnographers, and then the monks of Ireland, Wales, and Scotland who decided to write down hitherto oral traditions of their pre-Christian past for reasons that are open to debate–possibly to give themselves a native analog to the Old Testament, a history of their world before they saw the light. Possibly presenting druids as local versions of the pagan Roman authorities who persecuted the early continental Christians (although it should be noted that the druids who turn up in Irish hagiographies are more apt to be martyred by the saint under discussion, rather than vice versa). Or possibly because they just couldn’t pass up a good story, no matter what the religious underpinning.

In the medieval period, though, druids per se disappear from the literature and are replaced by magicians (hey there, Merlin!), bards (thanks for stopping by, Taliesin!), radically unorthodox “saints” (hi, Brigit!), and crazed kings (Sweeney, get out of that tree this instant!). Likewise, the Latin and Greek writers who noted the characteristics of Iron Age Celtic society seem to have disappeared from monastic reading lists. As far as I can tell–and I am more than happy to be corrected on this matter–medieval Irish and Welsh monks were not sitting around the scriptorium reading and copying Caesar’s Gallic Wars, taking careful note of the religious customs of the French Gauls, and then constructing stories about their own Irish or Welsh ancestors that bore tantalizingly evocative similarities to classical works about people they probably didn’t realize they were related to. Nor did they deliberately devise stories about their ancestors in order to manufacture startling resemblances to archaeological discoveries that would not be made for some 400 years or more. Whoever wrote down the story of the shoe-making Llew Llaw Gyffes in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi in the White Book of Rhydderch in the late fourteenth century is really unlikely to have been aware that, some 1200 years earlier, a guild of Celtiberian shoemakers had worshiped “the Lughs” in north-central Spain.

It still seems to me–despite several decades of archaeological disavowal of “Celticity”–that the archaeological finds of the modern age in Ireland, Britain, and France; the medieval literature of the Welsh, Irish, Scots, Bretons, Manx, and Cornish; and the observations, however biased, of literate contemporaries of the Iron Age inhabitants of those same areas all cohere into a reasonable whole. Yes, there are geographic and temporal variations; there are things in the archaeological record not explained by literature and vice versa, but all in all, it seems to me that the literature is talking about a people as unified as, say, modern Americans. Which is to say that sometimes groups of people behave in big, generally similar ways and sometimes in small, locally unique ways, but being small and unique does not obviate the big similarities.

EARLY MODERN DRUIDS

So, where was I? Oh yes, druids. And the changing eternal.

To get 1066-and-All-That-ish about it, the Renaissance happened, and everyone was reading Caesar like nobody’s business. And–now that they realized that their world had had, so to speak, layers of occupation over the years–starting to wonder what all those big lumps of stone hanging around the landscape were about, not to mention those hills that, now you come to think about it, really look at them and think about it, didn’t look all that … natural. So they started digging, and trying to correlate what they dug up with what had been written so many centuries ago. Voila: archaeology.

Also, in other breaking news, voila: the Church of England. Enter, among others, William Stukeley.

![What the eighteenth century thought a first-century druid looked like. Meta enough for you? From William Stukeley's Stonehenge (1740). William Stukeley [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://leslieellenjones.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/abritishdruid.png?w=190&h=300)

What the eighteenth century thought a first-century druid looked like. Meta enough for you? From William Stukeley’s Stonehenge (1740).

William Stukeley [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Stukeley (1687-1765) was, first, a doctor; second, an antiquarian-cum-archaeologist; third, an adherent of Speculative Freemasonry and founder of Neo-Druidism; and fourth, an Anglican clergyman (please notice the order here–he took orders

because of his archaeological and “druidic” interests). Following the path laid by John Aubrey in his

Monumental Britannica (written in manuscript between 1663-1693), Stukeley dug at both Stonehenge and Avebury, as well as other stone circles and megalithic sites, between 1718-1725 and began propounding his theory, in his

Stonehenge: A Temple Restored to the British Druids (1740) and

Avebury: A Temple of the British Druids, with some others, Described (1743), that these monuments were the work of druids–and that druids were proponents of an “Abrahamic religion” and therefore, in essence, wandering Jews who were just waiting for Christ to come around so that they could turn to the true faith. (

Henry Rowlands was another early archaeologist-clergyman who came to a

similar conclusion.)

Stukeley was the big name in this line, but it is here, in the early modern period, roughly between the reigns of Charles II and George III, that the idea that the druids are responsible for Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments arises and worms its way inextricably into the public consciousness. This is when men in fancy dress start performing dawn rituals at Stonehenge on the Summer Solstice. Stukeley made the perfectly scientific observation that a Roman road cuts through the site of Stonehenge, and therefore Stonehenge must predate the Roman occupation of Britain; since, as far as anyone knew at the time, the only people in Britain before the Romans were the Celts, this “obviously” religious monument must have been built by and for the Celtic clergy: the druids. That was Stukeley’s conclusion, and he ran with it. And many still run with it, to this day.

Further reading

I am, of course, fond of my own Druid Shaman Priest: Metaphors of Celtic Paganism, which is out of print but still floating around. For further thoughts on the subject of druidic human sacrifice, my thoughts are laid out at length in a paper I presented at the UCLA Celtic Colloquium in 2000, titled “‘Hi, My Name’s Fox’?: An Alternative Explication of ‘Lindow Man’s’ Fox Fur Armband and Its Relevance to the Question of Human Sacrifice among the Celts.”

Ronald Hutton’s books on British paganism, real and imagined, are the go-to books on the subject; Blood and Mistletoe: A History of the Druids in Britain is obviously the place to start, but I’m also quite fond of The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (where it all started) and The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft.

It seems like every time you turn around, they’ve discovered something new about Stonehenge and environs. The most recent book by the guy in charge of the excavations is Stonehenge–A New Understanding: Solving the Mysteries of the Greatest Stone Age Monument by Mike Parker Pearson.

![Rosmerta and Mercury, a cute couple. From Eisenberg, Donnersbergkreis, ca. 200-250 C.E. By QuartierLatin1968 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://leslieellenjones.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/mercurius_rosmerta_histmuspfalz_3513.jpg?w=225&h=300)

![What the eighteenth century thought a first-century druid looked like. Meta enough for you? From William Stukeley's Stonehenge (1740). William Stukeley [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://leslieellenjones.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/abritishdruid.png?w=190&h=300)

![Prince Madoc Leaving Wales, by William Cullen Bryant / C. Scribner's Sons (1888) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://leslieellenjones.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/1024px-madoc_leaving_wales_depiction.jpg?w=300&h=174)

![Humphrey Llwyd's Cronica Walliae, the first printed reference to Madoc's voyage. By David Powel [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://leslieellenjones.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/history_of_cambria_1811_cover.jpg?w=300&h=291)

![The Gundestrup Cauldron. You could spend a lifetime thinking about the imagery on this thing. Nationalmuseet [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://leslieellenjones.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/gundestrupkarret.jpg?w=696)