I created these clouds by turning the texts of Pwyll and Owein (trans. Sioned Davies) into word lists, sorting them, and cleaning them up by 1) eliminating pronouns, prepositions, articles, and conjunctions; 2) turning all verbs to present tense; 3) consolidating similar terms (such as using kingdom for both realm and kingdom); and 4) deleting words that occur fewer than three times for Pwyll and four times for Owein (which, as a longer story, has a larger vocabulary).

created in Wordle (wordle.net)

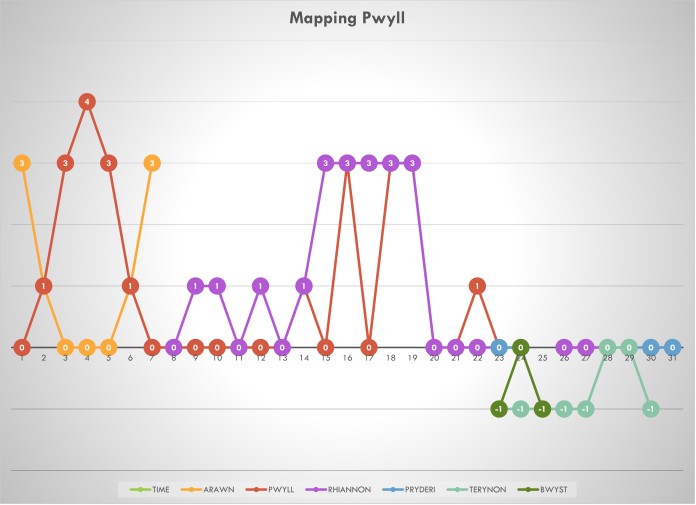

As you might expect, our hero, Pwyll, is the name most mentioned, but far and away the commonest verb is a form of say, which reflects the amount of dialog in the story. Come, give, and see are important verbs, followed by get, know, sit; court, kingdom, and horse pop out as important nouns. Rhiannon and Teyrnon are the most important names after Pwyll, and Annwfn and Dyfed are about of equal weight as locations. There is also a lovely little cluster of company, carouse, and feast. Altogether, the cloud gives the impression of a story concerned with rulership and family relationships, which is hardly surprising to anyone who has read the First Branch, but also concerned with the passage of time (the size of year, for instance), and ideas about friendship and communication.

Here is the cloud for Owein:

created with Wordle (wordle.net)

Obviously, while the name of the main character is important in both stories, in Owein, our hero’s name is more important than anything, while in Pwyll, speaking (“say”) is even more important. The little cluster in the right center of knight, lion, and horse confirm that, like Chretien’s version, this is very much a story about a the Knight with the Lion. The big vocabulary is of an upper class world of knights, countesses, castles, and the ever popular brocaded silk; the characters come, go, and take, but they also hear noises (an over-all terms for shrieks, yells, wails, and other sounds), look, know, and fight.

I have to admit, however, that as I was creating the lists that underlie these clouds, I was increasingly aware that the frequency of some words was skewed by translation. I think Davies often used different English vocabulary to translate the same Middle Welsh word just to keep the English text from becoming tedious–which is, after all, a valid choice for a translator. The reason I didn’t go straight to analyzing the original Welsh texts is that I wanted to do a test run in English to see if it was useful. Creating word clouds entails making a regularized list of each instance of a word’s occurrence, which in turn involves a lot of sorting into alphabetical order. This is a long and tedious task in modern English; it is, to put it mildly, exponentially more work in Welsh due to initial mutation, and even worse in Middle Welsh texts with their unstable orthography.

Word clouds look snazzy, but for analyzing Middle Welsh prose texts, they may be more trouble than they’re worth.